Literary horseplay

The record of the civil and military experience on St Helena during Napoleon’ exile has been both informed; influenced and often prejudiced by the vast literature that has developed since his death in exile. This has been almost universally hagiographic in tone. That is, Napoleon’s exile, life and death on the island has been painted in glowing terms.

The literature has been overwhelmingly favourable to Napoleon and his ‘plight’ and has been hostile to the record of the British Government in London (See also ‘The Holland House Set’ in the London topic) and of their representative on the island, the Governor, Sir Hudson Lowe (See also ‘Sir Hudson Lowe’ in the St Helena topic).

The accounts had their origin in the resentment felt by the French for their defeat after nineteen years of war that had led to their defeat in 1815 and to Britain’s new-found global domination by land and sea. Only the USA stood out against Britain in the West.

The early nineteenth century also saw the beginning of a number of freedom movements at home and abroad whose adherents believed the stories of his mistreatment by the British.

French republicans, still loyal to Napoleon, harboured a deep hatred of the British and of the restored Bourbon monarchy and vowed revenge for what they believed as his harsh treatment. Napoleon remained an enduring hero for millions whose campaigns across Europe had freed them from the tyranny of ancient monarchies and the hegemony of the Church of Rome.

The United States of America smarted from the war of 1812 against the British (See also ‘The War of 1812 on the Chesapeake’ in the Empire of the Oceans topic) and the people of the Americas still resented the British invasions of the Argentine in 1806 and 1807.

In Britain itself, the Government, which had looked on in horror at the French ‘terror’, now regarded the growing demand for domestic political reform at best seditious and at worst traitorous and associated Napoleon with all their troubles.

There were two particular issues in the literature on which hatred of the British was focussed at home and abroad. The first was on the health of Napoleon and the accusation, made very soon after his death, that the British had murdered him by the administration of poison.

The second was the character of Sir Hudson Lowe, the British appointed Governor, whose behaviour was considered to have been mean spirited and designed to make the prisoner’s life – and death – as unpleasant, and as inevitable, as possible.

There is a very small literature in defence of British policy and this is drawn mainly from Sir Hudson Lowe’s personal correspondence whilst governor – and even these have been used to both attack and defend his decisions.

Some of the main literatures have come from disaffected individuals who served on the island during the time of Napoleon’s exile and who wrote for political and monetary gain. One of the most prominent of these was the account by the Irish doctor, Barry O’Meara, a naval surgeon who sailed on the Northumberland with Napoleon into exile and became close to him thereafter.

O’Meara was accused of delivering illicit mail to Napoleon contrary to Sir Hudson Lowe’ orders; of spreading inaccurate gossip from Longwood, Napoleon’s residence, about his harsh living conditions and of insubordination. O’Meara was court-martialled and dismissed the Service but when he had returned to England he published a scurrilous account of his time on St Helena, Voice from St Helena, that caused the Government no end of political trouble from the Whig-Liberal interest.

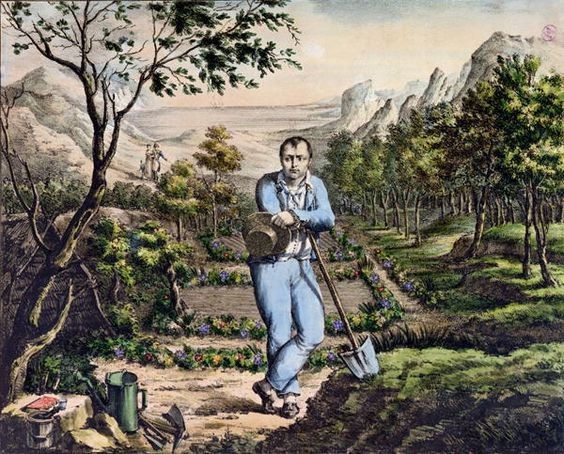

Less problematic at the time, but of significance since, have been accounts by members of the Balcombe family, most notably by Betsy, William Balcombe’ daughter, who wrote an account of her experiences on St Helena at the time of Napoleon’s imprisonment entitled Recollections. This drew a sympathetic picture of Napoleon with descriptions of his daily life in exile and social inter-actions, including his gardening activities.

Other influential accounts included the diary kept by Sir Hudson Lowe’s military secretary Major Gorrequer who kept a daily record of events in code that were mostly disobliging, particularly about Governor Lowe’s wife.

Contemporary French accounts written by members of Napoleon’s suite and household after they had returned to Europe following his death were universally sympathetic.

The overall impression given by the literature written about Napoleon’s exile on St Helena is that the ex-emperor’s behaviour had been exemplary and that the British had behaved damnably.

See also “Salute Me When You See Me” by Michael Fass in Bookshop.