The Charter Companies

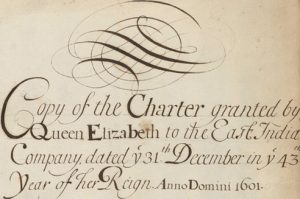

Another key aspect of trade development was a device created by the King in Council, the ‘Charter Companies’. These bodies were financed by private individuals and licensed, or chartered by the monarch to carry on trade in a specific territory. They included the Hudson Bay Company, the East India Company and the Atlantic Company. They had wide powers and exclusive rights to rule their allotted territories so long as they remitted a proportion of their takings to the Treasury each year – and all done with no investment whatsoever from the State! As a result of these arrangements and as world trade grew, both King and Company became immensely rich.

Another key aspect of trade development was a device created by the King in Council, the ‘Charter Companies’. These bodies were financed by private individuals and licensed, or chartered by the monarch to carry on trade in a specific territory. They included the Hudson Bay Company, the East India Company and the Atlantic Company. They had wide powers and exclusive rights to rule their allotted territories so long as they remitted a proportion of their takings to the Treasury each year – and all done with no investment whatsoever from the State! As a result of these arrangements and as world trade grew, both King and Company became immensely rich.

The Honourable East India Company (EIC) with its head office in Leadenhall Street became the most powerful of these developing almost national government status to rule over its vast territories in the East.

Trade was disrupted for many years by the war in Europe against France and its allies that lasted 19 years and which reached the farthest corners of the world but at its end Britannia was left the dominant power in the Atlantic and elsewhere.

The Dutch had been removed from what became South Africa, the French from its island dominions in the West Indies and the Spanish from its colonies in South America.

The Atlantic World was now almost entirely British.

The only exception to this was the United States of America whose privateers, sailing from Atlantic East Coast ports carried ‘letters of marque and plunder’, that enabled them to plunder cargoes from ships of every nation. This led to the war on the Chesapeake in 1812 and the burning of the White House in Washington.

Whilst Britain had reduced its Fleet drastically at the end of the Napoleonic wars, it nevertheless had absolute command of the Atlantic and there was no prospect that Napoleon would be rescued by sea.

The only traffic allowed to and from the island of St Helena during the time of Napoleon’s exile and imprisonment was either East India Company vessels on their way out to, or returning from, the East Indies and the guard ships of the British Navy.

The gardens of St Helena

The East India Company had the lease of St Helena from the British Government in London and used it as a re-victualling station for its ships, growing crops in its gardens that were cultivated throughout the island. There was also a ships chandler business owned and managed by William Balcombe, the Company’s agent, who lived at The Briars, where Napoleon was put up when he first arrived. A permanent naval squadron was anchored in the roads at Jamestown, the capital, that was responsible for the security of the seas around the island. All approaching vessels were boarded and their cargo, passengers and crews were inspected. Both naval and Company ships carried mail to and from London and supplies were delivered by ship out of Cape Town for the garrison.

With naval squadrons stationed at Jamaica in the Caribbean and at Halifax in Nova Scotia on the eastern side of the Atlantic and the port depot at Simons Town in South Africa, serving both the South Atlantic and Indian oceans, the empire of the seas was almost complete. Britannia ruled the waves indeed!

Lieutenant James King was my grand uncle (X4) who sailed in Captain James Cook’s Resolution as Second Lieutenant in 1176. Following Cook’s death, and that of his successor, Charles Clerke, King was appointed to command Cook’s flagship HMS Discovery and bring her home. He was born in Clitheroe, Lancashire in 1750 where his father was Rector and entered the Navy in 1762 at the age of 12.

After serving on the Newfoundland station in Canada, he was placed on half-pay in 1773 and studied science in Paris and at Corpus Christi College, Oxford where he was taught by Thomas Hornsby, professor of astronomy, who recommended him to Cook.

When King returned to England, he wrote the official account of Cook’s last voyage in three volumes and served in the English Channel and later in the West Indies. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1782 and died at the age of 34 in 1784.