How Britannia came to rule the Waves and became the empire of the oceans.

At the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, the Atlantic World was not the only empire of the oceans. The world of the Mediterranean Sea was much older with its echoes of Greece, Rome and Constantinople. The Pacific world in the East had long been familiar to explorers and traders.

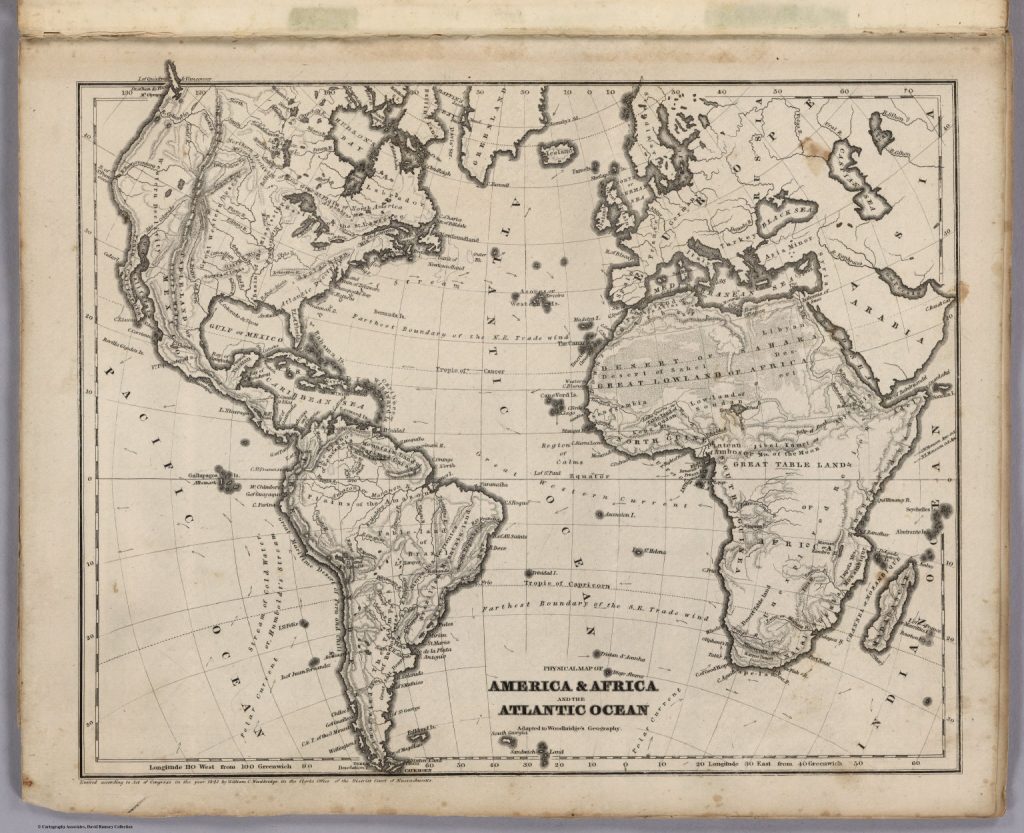

In 1815, the year of Waterloo, a glance at a map of the Atlantic showed Greenland at its top and Iceland lying below. On the right of the map was the Scandinavian archipelago; the islands of Great Britain with its most westerly point at Ballymullen in the West of Ireland and the European mainland with its southerly tip at Gibraltar just off Spain. To the south lay the African continent. On the opposite side of the ocean lay North and South America. In the centre was the vast Atlantic Ocean.

Maps produced in Britain at the time showed the principal trade routes across the Atlantic with thick lines drawn east to west between Liverpool and Halifax, New York and Baltimore. More lines reached out to the Caribbean islands from Bristol, Lisbon and Cadiz and down the coast of West Africa via Madeira or Ascension, before crossing the Atlantic to Bahia, Montevideo and Buenos Aires in South America.

The early explorers

There was little to see in the vast South Atlantic except for St Helena.

At the southern-most tip of Africa was the Cape of Good Hope and opposite at the tip of the Americas, Cape Horn. The earliest navigators left Europe in the late 15th century on their voyages of exploration. John Cabot (c. 1450-1500), an Italian, was commissioned by King Henry VII of England to find a route through the northern ice but found himself instead off the coast of Newfoundland and its rich cod fishing grounds where, in 1497, he is believed to have discovered America.

Ferdinand Magellan (1480-1521), a Portuguese mariner, sailed from Spain and discovered the East Indies in c. 1519 and Vasco da Gama, who died in 1524, was sponsored by Henry the Navigator, King of Portugal to find a passage to the fabled East.

Magellan set off westwards down the coast of Africa, crossed the Atlantic and sailed around Cape Horn and into the Pacific Ocean reaching Cochin in India from the west. Da Gama did the same initially but then turned eastwards around the Cape of Good Hope and sailed across the Indian Ocean reaching landfall at Bombay.

Both men returned with tales of the fabulous wealth to be found across the oceans that triggered relentless competition amongst the European nations.

First, it was Portuguese and Spanish sailors who developed these routes that became the arteries of trade and established their nation’s quayside factories in India and started the race for its conquest.

Goods purchased by agents in the interior were stored in these warehouses before being assembled into bulk loads and shipped back to Europe in great convoys that provided protection from uncertain weather and attack by pirates.

Next, it was the Dutch who developed an empire in the East Indies and dominated foreign trade with imports to the West of exotic spices such as pepper and cinnamon that made the tasteless salt and vinegar diet of northern Europeans more palatable.

Then it was the turn of the Bourbon French monarchs to establish an empire in northern Canada where furs, pelts and salted cod were traded in return for sugar and in India for silks and cottons.

Finally, by the mid-18th century, and after long wars involving France, Holland and Spain, Great Britain began to acquire the greatest number of these routes, together with their factories and hinterlands, in North America, the Caribbean, Africa and the Far East and became the foremost and wealthiest empire that the world had ever seen. Britannia’s global reach was confirmed by James Cook’s voyages in the final quarter of the eighteenth century when he sailed across Pacific Ocean to land in Australia and New Zealand.

Britain’s global reach

Britain’s domination was made possible from its post-civil war settlement of 1688 and by its discovery of coal that fuelled an unparalleled industrial revolution. Coal and the use of steam drove up manufactures and, together with the availability of financial capital, produced an unprecedented increase in foreign trade.

Other influences that contributed to growth were the British Navy and the commercial acumen of the City of London’s merchants. Both before and during the Napoleonic wars, the British Navy had become the most powerful in the world with an industrial infrastructure that produced men of war at a phenomenal rate constructed in shipyards spread around its coasts. One of the country’s strategic imports was timber cut in its North American colonies and in Canada and shipped to the great Naval dockyard at Chatham on the Medway where warships were manufactured on a grand scale.