The war of 1812 on the Chesapeake between Britain and the United States of America could not have come at a worse time for Britain in the course of its long war with France. United States of America resisted the press and the Stars & Stripes flew over Fort McHenry.

If Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, that began in the same month, was successful and Tsar Alexander was defeated, the French Emperor and his allies would have no further opposition on continental Europe and would leave Britain to stand alone.

Whilst Wellington’s army, now returned to Portugal, had gained some early successes, there had been no decisive break-out that would remove French troops from Spain and enable the British to attack Napoleon on his own soil.

At the time when all of Britain’s resources were stretched to the limit and beyond, on the other side of the Atlantic President James Madison and the Congress decided to strike.

The direct cause of the war of 1812 was a set of Orders in Council issued by George III that had infuriated American commercial interests. The Orders were designed to prevent American vessels from trading directly with the European Continent, which Britain’s Navy had been blockading for the past six years as part of its economic war against the French that prevented imports and exports.

These Orders required American vessels to enter British ports before sailing on where their cargoes would be inspected to ensure that they were not carrying war materials that could be used by Napoleon’s armies and where they would be charged import duty as if their goods were destined for British consumption. The Orders would be enforced by the British Navy’s warships which would detain American vessels and bring them into home ports.

Letters of Marque and Plunder

However, there were additional reasons for the outbreak of hostilities between Britain and the Unites States.

The British Navy was running dangerously short of seamen after fifteen years at war and their notorious press gangs, known as The Press, had not only become increasingly active in commercial ports in the North Sea and the Mediterranean but had also begun to stop and search American ships on the high seas and to remove crew members who were forced to serve on HM ships. This was contrary to the law and custom of the oceans.

Ever since the end of the War of Independence, the United States had looked at Canada through envious eyes. For the country’s growing and land-hungry population – and for their political leaders – it was both obvious and inevitable that Canada would become part of the United States of America. ‘Oh! Canada’ sighed the members of the United States Senate whenever its name was mentioned in debate.

Finally, the Americans also looked westwards and southwards. Westwards towards the Great Plains with its thousands upon thousands of acres of potentially rich grazing lands ripe for exploitation and southwards into the Mississippi valley with the prize of the trade of New Orleans at its mouth.

The early campaign was focused mainly on the Great Lakes of the Canadian border where ill-prepared and poorly led American militia fought the more experienced British forces and their Indian allies. However, in a number of vicious and small-scale encounters on land by the opposing armies and on water by their navies, neither side was able to claim victory.

For eighteen months this stalemate continued whilst atrocities increased on both sides.

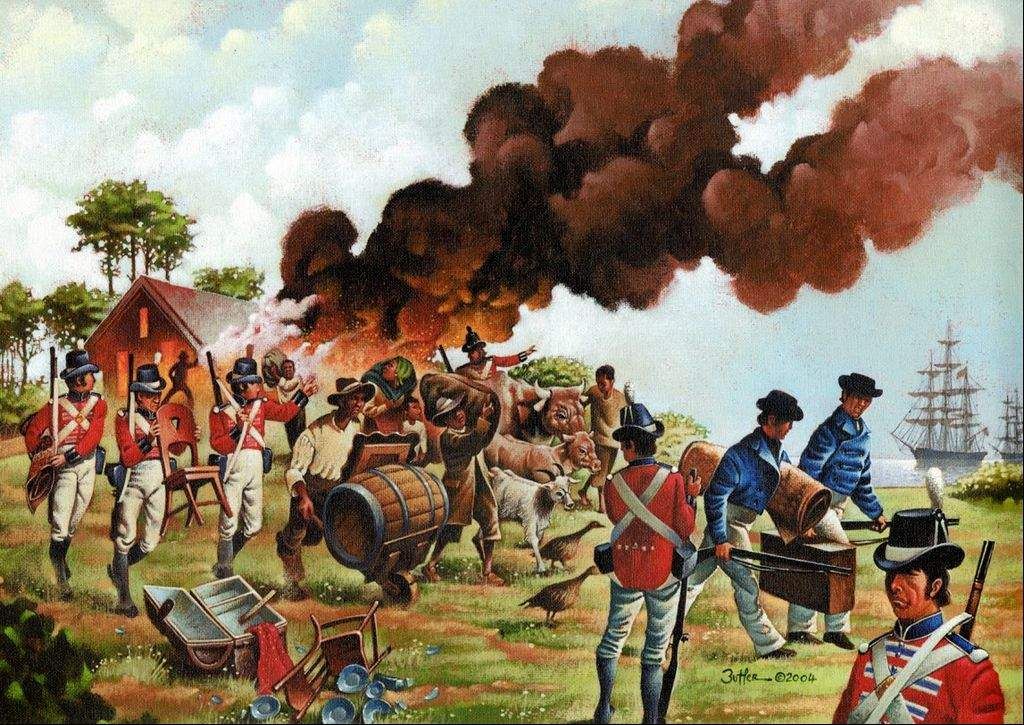

In an early skirmish at Queenstown the British lost their talented land commander, General Isaac Brock of the 49th Foot. and the Americans suffered defeat at the loss of Fort Dearborn. The British used their Canadian Indian allies – who regularly scalped and killed their prisoners – to terrify their opponents and the Americans, in their turn, left wounded British soldiers out in the open to die. In a particularly shocking episode during a raid at Long Point, Lake Eyrie, on the Canadian side of the border, the Americans had murdered its inhabitants before burning the entire village to the ground.

However, eighteen months later, in April 1814, after a dramatic reversal of fortune, the Allies had entered Paris and ex-Emperor Napoleon had been sent into exile on Elba. Britain could now release experienced troops from the European theatre and send them across the Atlantic to renew its efforts against the United States of America.

Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, the C-in-C of the Navy’s fleet in North America, received new orders from the Secretary of State for War, Lord Bathhurst, in June 1814.

The cost of insurance

The news of the behaviour of American troops at Long Point had reached London at the same time as a petition arrived in Parliament signed by over four hundred Glasgow merchants and their MPs. The petition complained at the loss of trade that they were suffering as a result of the actions of American privateers.

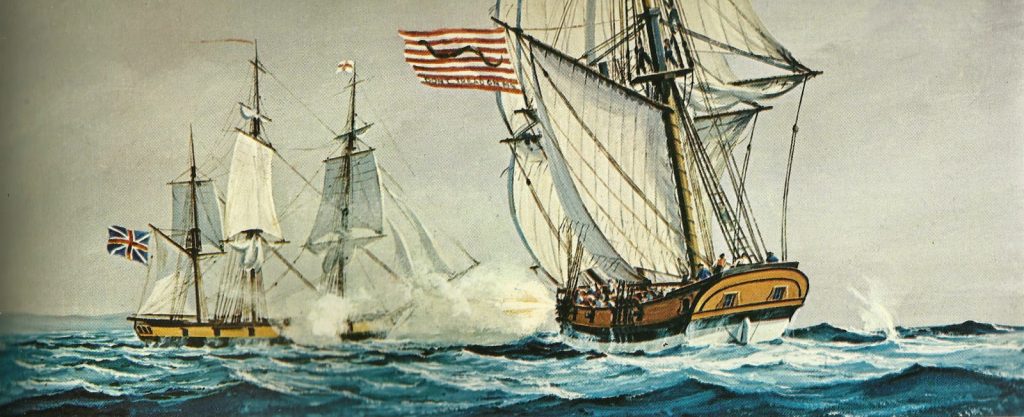

These privateers, holding ‘letters of marque and plunder’, issued by their government that excused them from potential charges of piracy, were in the habit of boarding British registered merchant ships and, after sailing them into American ports, sold their cargoes and either auctioned off or burned their ships. As further evidence, the merchants added, the cost of insurance at Lloyds now stood at an intolerable 16% of the value of each cargo shipped.

The most notorious of these privateers was The Damned Yankee – Captain Henry Deacon commanding – out of Baltimore, the home port of many of these seagoing bandits. She was a sleek, 3-masted schooner, one of the fastest afloat on the world’s oceans with a crew of over 140 seamen (See also Escape in the St Helena topic). She had already plundered more than 250 vessels and taken over 450,000 tons of cargo worth more than £2.6 million. As one of its revised war aims, the British intended to locate and destroy such vessels to act as an example of their total control of the high seas.

Cochrane was now ordered to use his forces to land troops along the coast of the North American seaboard and cause sufficient havoc to bring the United States of America to heel.

This could include, if he thought judicious, the occupation of the Nation’s new capital in Washington, and, it most certainly should include the capture of Baltimore, its greatest commercial centre; home to its privateers and to its most anti-British and pro-Federalist inhabitants.

Cochrane ordered his ships to rendezvous off the New England coast at Hampton Roads – the mouth of Chesapeake Bay – and summoned his naval and army commanders, Rear Admiral George Cockburn (who would later accompany Napoleon on HMS Northumberland into exile on St Helena in October 1815) and Major General Robert Ross (hero of the battle of Vittoria in 1813) to join him to discuss tactics on board his flagship HMS Albion.

Cockburn commanded 1,700 Royal Marines on board the fleet and Ross had a further 5,000 men on the same ships.